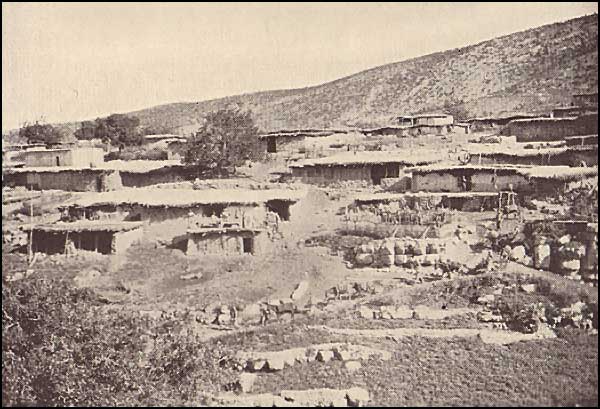

I know people who eat kebab every day, and I have often wondered how they can. Or rice and chicken and sauce, every day the same. Or just with sauce - soup, the Kurds call it, as in the picture. So boring! Where I come from, you can eat food from all over the world: Spanish, Italian, Asian and even Russian.

I know people who eat kebab every day, and I have often wondered how they can. Or rice and chicken and sauce, every day the same. Or just with sauce - soup, the Kurds call it, as in the picture. So boring! Where I come from, you can eat food from all over the world: Spanish, Italian, Asian and even Russian.Not only in restaurants; Western supermarkets also sell the ingredients and some pre-cooked meals. When I came to live in Kurdistan I had a major problem: the lack of the food stuffs needed to make a meal the way I like it. For that reason I simply stopped cooking. I was lucky to know two ladies who are good cooks, and the best when it comes to yaprach.

One problem for me is that the main meal is at lunchtime. After eating a lunch like that, no way I can concentrate on my work. Heavy lunches are bad for productivity.

Problem number two is the portions. Who can eat all of the xosi sham (see the picture below)? I hardly get half way. And the rest? Is just thrown away. Does anyone ever consider the waste? Not just the cost of the material, but also the time and energy that went into growing and harvesting the rice, feeding the animals used, the transporting of the food, and finally the cooking? To be wasted like that? It makes me feel guilty when I leave half my xosi sham. So whenever possible, I try to share the plate.

And another problem with these portions is that people eat too much. And put on weight, as in the Kurdish society hardly anyone exercises or does sports.

And another problem with these portions is that people eat too much. And put on weight, as in the Kurdish society hardly anyone exercises or does sports. And it's not even only the portions. The way the Kurdish rice is cooked, with quite a bit of oil, is also far from healthy.

Moreover: the change that came on the gastronomical field, is not a positive one. Fast food conquered the Kurdish towns. Young people have become addicted to hamburgers and fries. The results will show when the Kurds get the same problem as the United States has with obesity: too many people get too fat, and from a young age.

Being fat in Kurdistan is still seen as positive. It shows you have enough money to get well fed, and if your luck turns at least you have some fat to burn. The fact that it is unhealthy, and leads to heart attacks and other diseases, has not been well promoted.

It is high time that Kurds do realize that offering smaller portions is not impolite at all. No, it is considerate, as they do not want their guests to eventually die from overeating.

This column was published as a column in the Kurdish newspaper Kurdistani Nwe.